Modern marketing is increasingly shaped by short-term pressure. ROAS dashboards refresh daily, budgets shift weekly, and growth is often judged by how efficiently performance channels can convert demand. It works – until it doesn’t. Patagonia stands as one of the clearest counterpoints to this mindset; a brand built patiently, deliberately, and with a long-term view most marketers rarely get the chance to pursue.

That long game starts with philosophy, not platforms.

Yvon Chouinard’s Let My People Go Surfing isn’t a business book in the traditional sense, but it forms the philosophical backbone of Patagonia’s brand. It’s also a book that had a lasting impact on how I think about business and marketing. Chouinard writes that “the hardest thing for a company to do is to grow responsibly” – an idea that reshaped how I view growth and helps explain why Patagonia has never chased the short-term wins many brands rely on today. His views on growth, responsibility and consumerism make it clear that environmental values came first, marketing came later. Patagonia wasn’t designed to optimise short-term demand; it was designed to exist responsibly. In a world obsessed with scale, the brand became intentionally anti-short-term.

That philosophy was formalised in 2022 with the creation of the Patagonia Purpose Trust and Holdfast Collective. Ownership was structured not to maximise shareholder return, but to protect the brand’s values indefinitely. Profits serve purpose, not the other way around. That decision alone explains why Patagonia’s marketing feels different – it isn’t racing against quarterly expectations.

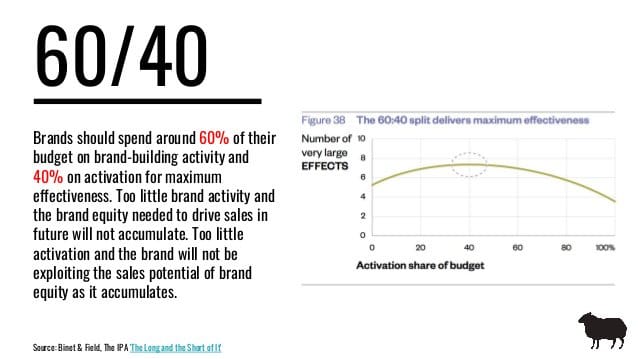

From a marketing theory perspective, this aligns closely with Les Binet and Peter Field’s The Long and the Short of It. Their research shows that long-term brand building drives sustained growth, while short-term activation delivers immediate results. The optimal balance, they argue, is roughly a 60/40 split for DTC brands – 60% brand building, 40% activation. When brands lean too heavily on activation, they risk brand decay.

The performance trap persists because it works early. Converting high-intent users delivers strong ROAS and quick wins, reinforcing budget decisions. But research consistently shows that performance marketing mainly captures existing demand from a small in-market audience, typically around 5% of the category. Once that demand is harvested, growth stalls. As privacy regulation and platform changes like iOS 14.5 weakened attribution, the cracks became harder to ignore. What looked like precision was often over-credited last clicks, masking the brand activity that created demand upstream. Without investment in brand, performance doesn’t scale – it just gets more expensive.

In Patagonia’s case, brand building is clearly defined through emotional storytelling, cultural relevance, environmental leadership and restraint. Activation still exists in the form of paid media, promotions and retargeting but it’s used sparingly and on Patagonia’s terms. The brand rarely discounts, avoids urgency-led messaging, actively discourages over-consumption, and invests in repair services. Binet and Field warn that excessive short-termism harms brands over time; Patagonia is living proof of the alternative.

The payoff is mental availability – another key concept in Binet and Field’s work. Brands grow when they’re easily recalled in buying situations, and emotional brand building strengthens that recall. Patagonia stays mentally available not by flooding feeds, but by consistently leading environmental conversations, showing up in outdoor subcultures, and standing for something stable and credible.

Patagonia’s visibility is built through presence, not promotion. Instead of traditional UGC, the brand documents its own team and long-standing athletes in the environments they care about – climbing, surfing, snowboarding and protecting wild places. Figures like Dave Rastovich don’t feel like endorsements, but extensions of the brand’s values, reinforcing a story that already exists rather than trying to create one.

Working a ski season in Hakuba, it’s hard not to notice Patagonia’s presence across the snow sports community. While trend-led brands cycle in and out, Patagonia remains trusted from park laps to backcountry strike missions. It’s not worn for hype, but for reliability. In environments where gear failure matters, Patagonia feels like a default choice, not a fashionable one.

I noticed the same pattern while surfing throughout France, where Patagonia wetsuits and boardshorts consistently showed up in the water. Not as statement pieces, but as dependable gear worn by people who surf often, in varied conditions – reinforcing the idea that Patagonia earns trust by showing up where performance actually matters.

Campaigns like Patagonia’s 2011 “Don’t Buy This Jacket” further reinforce this restraint. Launched on Black Friday with a full-page New York Times ad, it challenged consumers to reconsider their consumption altogether. Rather than chasing sales, Patagonia reinforced its commitment to durability, repair and reuse – later extended through initiatives like Worn Wear. It wasn’t a stunt; it was a reflection of how the brand already behaved.

This stands in stark contrast to many modern B2C brands. With 80% or more of budgets tied up in Meta and Google, early performance gains often plateau as scale increases. CAC rises, loyalty weakens, and growth becomes fragile. Performance-first brands don’t just struggle to grow, but they struggle to stop spending. Patagonia doesn’t face this problem because demand was built long before the checkout.

Patagonia doesn’t reject performance marketing – it simply refuses to let it replace brand. And in an era of rising costs and diminishing returns, that long game looks less like idealism and more like strategy.